Imagine, if you can, that corporations truly are like people. They would vary in their dispositions. Some would be selfish and short-sighted, caring only about their own immediate gain. Others would be more prosocial and far-sighted, genuinely caring about the world around them and willing to do their part to promote the common good. As with real people, the cooperators would be in danger of exploitation by the knaves, but they would also be able to protect themselves by banding together, establishing norms of proper conduct and punishing transgressors. That’s how individual cooperators manage to survive and even thrive in a Darwinian world. Why shouldn’t the same be true in a world of corporate people?

One person who is able to imagine this scenario is Per L. Saxegaard, a former Norwegian investment banker who decided to create the equivalent of a Nobel Prize to recognize enlightened business leaders. He does this through the Business for Peace Foundation, which was founded in 2007....

PLS: So, it struck me that what we need to focus on in business is to get these two curves, the “making money” curve and the “making a difference” curve, to come together. We need to make money while making a difference to other people; merging profit with a higher purpose, while acting ethically and responsible. We coined it to be businessworthy. All business people know the concept of being creditworthy. That’s about not losing other people’s money. Being businessworthy is about earning other people’s trust. You can’t buy trust. Others give it to you....Evonomics

Humanizing Corporations: A Nobel Prize for Enlightened Business Leaders

David Sloan Wilson interviews Per L. Saxegaard, the Founder and Executive Chairman of the Business for Peace Foundation

Also at Evonomics

It’s conventional wisdom in business circles today that corporate directors should “maximize shareholder value.” Corporations supposedly exist to serve shareholders’ interests, and not (or at least, not directly) those of executives, employees, customers, or the community. However, this shareholder-value dogma begs a fundamental question. What, exactly, do shareholders value?

Most shareholder-value advocates assume that shareholders care only about their own wealth. But it is increasingly accepted that the homo economicus model of purely selfish behavior doesn’t always apply. This possibility provides a challenge to the dominant business paradigm of “maximizing shareholder value:” the concept of the prosocial shareholder.

THE SOCIAL ANIMAL

The problem with the homo economicus theory is that the purely rational, purely selfish person is a functional psychopath. If Economic Man cares nothing for ethics or others’ welfare, he will lie, cheat, steal, even murder, whenever it serves his material interests. Not surprisingly, although homo economicus is alive and well in many economics departments, many experts today prefer to embrace behavioral economics, which relies on data from experiments to see how real people really behave. Behavioral economics confirms something both important and reassuring. Most of us are not conscienceless psychopaths....I can recall the look we gave each other when introduced to homo economicus in Econ 101.

We all thought, like WTF? Are people really like that.

It seemed nonsensical, then at least.

But as one is further exposed to conventional economics, one begins to think that people are actually like that.

How the Dominant Business Paradigm Turns Nice People into Psychopaths

Lynn Stout | Distinguished Professor of Corporate and Business Law at Cornell Law School

See also

Medium

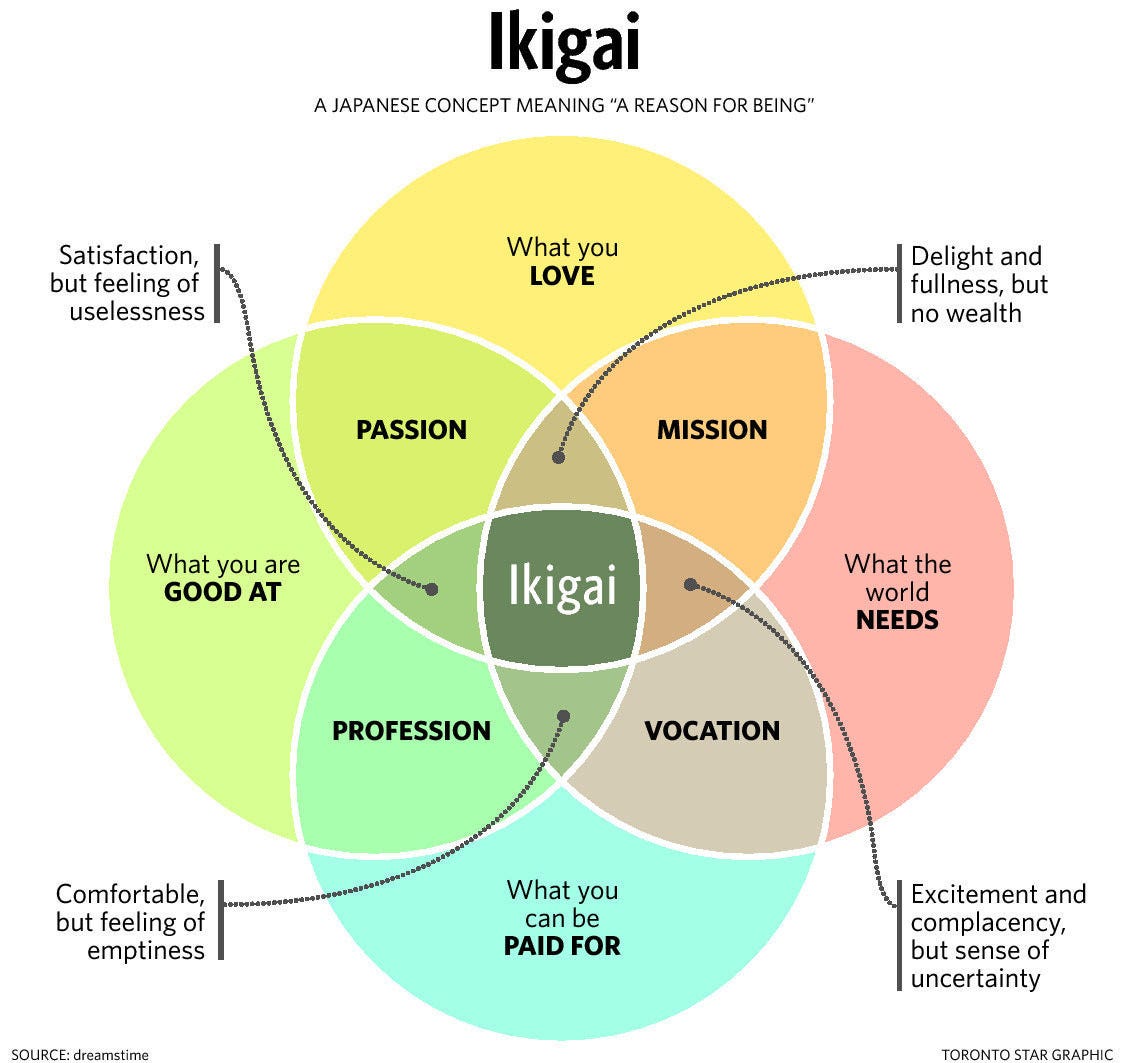

Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life Might Just Help You Live a More Fulfilling Life

See also

Medium

Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life Might Just Help You Live a More Fulfilling Life

Thomas Oppong

1 comment:

All business people know the concept of being creditworthy. That’s about not losing other people’s money.

"Loanable funds" alert. Actually, corporations are among the most so-called creditworthy of what is, due to heavy government privilege for the banks, etc., the public's credit but for private gain.

Without that government privilege for the banks, corporations would have had to issue much more common stock and thus "share" much more wealth and power.

Post a Comment